Even though Rose O’Neill has been gone for eight decades, her life lets her live: Across generations, continents and in the Ozarks, where the world-famous artist and Kewpie creator felt most at home.

That place is Bonniebrook, a tucked-away oasis in Taney County where O’Neill called home for much of her life.

Rose O’Neill, an artist of international fame, had long connections with the Ozarks. Her home, which was dubbed Bonniebrook, was one of her favorite retreats — and it’s a place visitors can explore today, too. (Courtesy of the Bonniebrook Historical Society)

“Why do I live in the Ozarks?” she was quoted as saying in 1938 in the Kansas City Star newspaper. “Really because I loved the rugged, rascally beauty. Besides, I have a spiritual affinity for ‘Bonnie Brook.’”

Although she frequently left the region – for work, or for extended stays at her other homes in places like Italy and New York City — the oasis lovingly named for its crystal-clear, rambling stream is where her heart lived, and its where her body has remained since her death in 1944.

Bonniebrook is located near Day, a small, defunct community in rural Taney County. O’Neill’s family moved to the Ozarks in the late 1800s and built the sprawling mansion.

Located just along Highway 65 between Branson and Springfield, it’s hidden in the middle of plain sight. Visitors can tour the home – not the original, which burned in 1947 and was rebuilt through dedication and donations in the early ‘90s – museum, and gift shop.

But it’s also in need of help. About 30 years after it opened, the historical site needs some big-ticket upgrades to continue keeping O’Neill’s legacy alive.

“We're having to rack our old ways and brains to try to reach the younger crowd and pull them in here,” says Connie Pritchard, president of the Bonniebrook Historical Society, who recently took over from longtime leader Susan Scott. “It's exciting, but it's also stressful at the same time, because we do have a lot of needs.”

The History of Bonniebrook

Rose O’Neill’s life began in June 1874 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. According to information from the State Historical Society of Missouri, she was one of six children born to William Patrick Henry and Alice Cecilia Asenath Senia Smith O’Neill.

Her interest and self-taught skill in art emerged at an early age. As a young woman, O’Neill went to New York City with a stack of sketches and successfully proved her skill.

“She brought her self-taught drawing skills to New York City at 19, staying in a convent so she wasn’t all by herself in the big city, and meeting editors throughout the day at the city’s publishing offices,” notes an article in Smithsonian magazine from 2018. “Much to the likely shock of the mostly men editors, O’Neill took meetings with several nuns in tow.”

It wasn’t long before her talent was known – even though it might not have been as clear as to who was behind the artwork. It’s said there was a period when she was told not to sign her name.

“She wasn’t allowed to sign her first name to her illustrations when she started out because ‘Our readers won’t like that a woman did it,’” says Gloria Cowper-Jen, a Bonniebrook board member, sharing what publication leaders told O’Neill in her early years. “She just really didn’t let anything get in her way. She was really a genius in a lot of respects.”

Writing, illustrations, fine art and sculpting led the way for her entrance on the national stage.

“By her early twenties, O’Neill was nationally known for her illustrations in popular magazines such as Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and Woman’s Home Companion,” notes information from the state historical society.

In 1906, she was in Paris to study the art of color, and four images she created were accepted into the Paris Solon, noted an article in the Springfield Daily Leader:

“This is an honor that falls to but few artists in a generation, and the women, especially American women who have achieved this pinnacle of artistic fame might almost be counted on the fingers of one hand,” the paper noted.

That start led to her distinction as “the highest-paid female illustrator in America” by 1914, the state historical society’s info shares.

Part of that legacy was built through her Kewpie dolls, which were introduced in 1909.

The first image was published in the Ladies Home Journal, and five years later the physical dolls made their entrance.

“The Kewpie doll is said to make everybody happy — it possesses the jubilant magic which produces a smile on the beholder’s countenance,” recorded the Times-Democrat out of New Orleans in 1913. “It has gained an immediate popularity and is being employed for many purposes besides that of a children’s toy — among others as a dinner favor.”

Dolls weren’t the only Kewpie creations. Other items included toothbrushes, comb and brush sets, and candlesticks, and lamps and silverware. At one point, there were even Kewpie radiator caps for automobiles.

“Before the end of World War I, there were about 30 factories turning out the dolls. These, too, were greeted with great enthusiasm, with many thousands of the flirtatious little figures sold, making O’Neill a millionaire and America’s highest paid illustrator in the 1920s.”

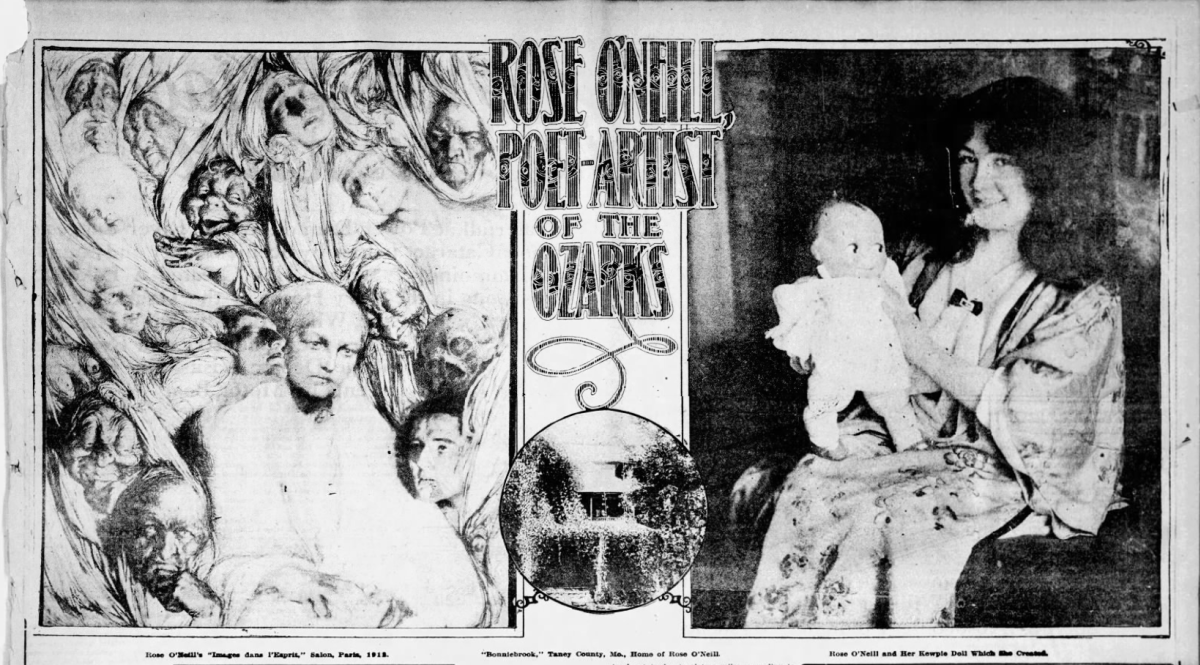

Rose O’Neill was featured in a 1913 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (Courtesy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

Rose O’Neill was featured in a 1913 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. (Courtesy of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

That distinction wasn’t the only one O’Neill held in her day. Married and divorced twice, she was an advocate for equal rights along both gender and racial lines. Just one example: In November 1914, Kewpies were even dropped from the sky, wearing small parachutes, during a flying demonstration to support women’s right to vote.

“After all, it’s quite time that some decisive stroke was struck for the freedom of women not only relative to the suffrage question, but on other matters,” she was quoted as saying in 1915 in the Springfield Republican. “The first step is to free women from the yoke of modern fashions and modern dress. How can they hope to compete with men when they are boxed up in clothes that are worn today?”

She practiced what she preached: In photos, she’s often shown wearing long, flowing robes she called her aura.

“I have always reveled in being unbuttoned and barefoot,” she said to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter in 1937.

The Building of Bonniebrook

Bonniebook wasn’t where O’Neill began her creative journey. Her family moved there in 1893, while she was in New York pursuing her career, notes a 1990 article in OzarksWatch magazine. Even though she didn’t grow up in its hills and hollows, that Ozarks oasis was where her creative heart found a place to call home.

In 1909, it was also where the world-famous Kewpie dolls were born.

“I think it’s one of Missouri’s most wonderful hidden gems,” says Terri Duncan, a Bonniebrook board member. “You think about her coming across her in a wagon; she was probably 19 years old. That’s pretty amazing, especially for those days and times.”

According to the National Register application, she had a villa on Italy’s Isle of Capri, a townhouse studio on Washington Square in New York City – and was the namesake Rose of Washington Square of Ziegfield Follies fame – and a stucco castle in Westport, Connecticut.

But, it also noted, “she loved her home at Bonniebrook the best.”

Rose O’Neill is shown at Bonniebrook. (Courtesy of Bonniebrook Historical Society)

The sprawling, 14-room mansion near the bubbling creek was far removed from the rest of the world. The trek to reach the retreat was documented by the Post-Dispatch in a full-page article dubbing O’Neill the “Poet-Artist of the Ozarks” in 1913:

“You start by crossing Roark on a rope ferry. Roark is supposed to be a creek, but no Ozarker adds that word. It is the only stream in that section, except the White and James rivers, which is not named for some beast or bird.

“After Roark you ford Bee Creek a few times, Bull Creek a few more times, Bear Creek a great many times, and finally reach Bonniebrook. Bear Creek, by the way, is the Taney County stream so crooked that it is noted chiefly as crossing itself four times in five miles.

“If you do not get irretrievably lost in trying to follow Bear Creek’s gyrations you will touch at last the dim trail that leads to Poe’s Ultima Thule — out of space, out of time. Allight, swing open an iron gate, and there, a few rods ahead of you is the home of Rose O’Neill.

“You come across it unexpectedly, for the big frame house is painted green, to consort poetically with the forest greenery that environs and overwhelms the dwelling. These trees grow flush up against the house. There is one giant catalpa, in full and fragrant bloom this Junetime, which brushes and caresses the windows of the artist’s studio at the top of the house.”

The destination also reflected O’Neill’s unconventional life of her day and age. It was a refuge for other notable Ozarkers of the day, including regional expert Vance Randolph. He and O’Neill were good friends; today, a collection of their correspondence is held in the Ozarkiana Room at College of the Ozarks.

It’s also worth noting that O’Neill was generous to a fault, which led to periods of poverty in her own life. At certain times, friends arrived at Bonniebrook and stayed for long periods of time.

Just one example: Later in life, “she couldn’t afford to pay her caretaker, so she paid her in furniture,” says Yvette Strick, a board member for the Bonniebrook Historical Society.

“I just love the fact that she was so giving and loving. She ended up losing everything that she had because she was a philanthropist who couldn’t manage her money.”

The Demise and Rebirth of Bonniebrook

O’Neill died in 1944 at age 69. She suffered a stroke and her health took a rapid decline, Pritchard says. The famed artist lived her last days at the O’Neill home in Springfield, which today is part of the Drury University campus. Her death was documented in newspapers across the country. But sentiment felt strong in the Taney County Republican, which documented O’Neill’s death:

“A nationally known and noted person is dead — not that she desired or sought publicity, for she did not. Her way of life was simple. We would amend our statement, for she was internationally known.

“Rose O’Neill died today in the home of a nephew in Springfield. But during her life she gave to the world a bit of her spirit that will endure. Her writings were of the nature that tore the veil asunder to let the character act as they will.”

On her death certificate, it asks for “usual” residence and occupation, but the questions reflect her unusual life: She was an “artist and writer,” and although it wasn’t a town as the form requested, her residence was listed as “Bonnie Brook.”

The Bonniebrook Homestead was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.

It’s where she was buried: In a small cemetery surrounded by members of her family. As the Taney County paper put it, “As simply as she lived — she died.”

O’Neill’s death was closely followed by another: That of her beloved Bonniebrook home, which went up in flames in January 1947.

“Picturesque vine-covered ‘Bonniebrook’ — the three-story, 14-room house deep in the Ozarks hills near Day, Mo., in which the late Rose O’Neill created the famous Kewpie doll — was in ashes today,” noted the Springfield Leader and Press about the house’s demise, which also said that one of O’Neill’s brothers still lived at the house at the time it burned.

For years, the property languished, but interest in O’Neill’s work remained. The International Rose O’Neill Club – today known as the International Rose O’Neill Club Foundation – was founded in 1967; according to its website, the organization’s purpose “is to preserve the memory of Rose O’Neill and inform the public about her works, and to promote the cultural arts.”

(A key event tied to the club is Kewpiesta, an annual gathering of devoted fans. While attendance isn’t as high as the thousands that once attended, 2025’s theme has already been announced: From April 30 to May 4, “Kewpies on the Farm” will come to Branson.)

More than 30 years after O’Neill’s death, the Bonniebrook Historical Society also came to be.

“It was basically formed to rebuild and restore the home and all the things that were left as evidence of Bonniebrook and the O'Neill family,” noted Lois Holman, former president of the society, in an interview for OzarksWatch magazine in 1990. “In 1975, the Rose O'Neill Club was going strong and attracting people from all over this country and some foreign countries. Some of the members decided that the Bonniebrook homestead should be developed and the home rebuilt, so they formed the Bonniebrook Historical Society.”

It took nearly two decades, but by the early ‘90s, their mission was complete. With the aid of photos and memories – no architectural plans were found – Bonniebrook was rebuilt. In addition to the home, painted in a peaceful shade of green, a large visitors’ center, gallery and gathering spaces were also added.

Today, visitors are still welcome to visit the home and gallery during its opening season April through October. All revenue helps support the site and its work. In addition to tickets, annual memberships are available, and items are for sale in the gift shop.

Bonniebrook today and tomorrow

About 30 years have passed since the “new” Bonniebrook opened to the public, and nearly 50 since efforts began to rebuild the heart of O’Neill’s physical world – one that exists within another much different and farther removed from the one where her work began.

Recognition still comes – and, in some ways, perhaps is in a revival from where it was a few years ago. Locally, her work was the focus of a 2018 exhibition at the Springfield Art Museum. On a larger scale, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2019, and was recognized with the aforementioned Will Eisner Award in 2022. Her work is also part of the Smithsonian. And Kewpies keep going, too: The trademark for their impish design is owned in Japan.

But while accolades help keep her memory alive, they do not help pay the bills at Bonniebrook, where a group of dedicated volunteers are diligently working to care for the aging structures.

“Did they decide to set money aside for future repairs? No. We’re finding ourselves, I’ll just be honest with you, in a pickle,” says Pritchard.

Bonniebrook Historical Society leaders include, from left to right, Gloria Cowper-Jen, Terri Duncan, Yvette Strick and Connie Pritchard.

Bonniebrook Historical Society leaders include, from left to right, Gloria Cowper-Jen, Terri Duncan, Yvette Strick and Connie Pritchard.

Pritchard recently took over as president of Bonniebrook, but her connection to the historic site isn’t new. Her grandparents’ land was adjacent to Bonniebrook, leading to ties that fire and time haven’t broken.

Her great-aunt was O’Neill’s housekeeper for years. Her grandfather also worked for O’Neill, helping with odd jobs around the property, and ultimately rediscovered the cemetery after it became overgrown years ago.

“Rose would play a game with him when she knew my grandpa and dad were coming,” Pritchard says of her dad. “Rose would put orange slice candy on the banister. And he knew, if he kept finding pieces of orange candy, he had to keep climbing the flights of stairs. He usually found her in on the third story in the studio.”

In fact, it’s those connections that helped lead to some of the home’s furnishings today. After O’Neill gave them to people like Pritchard’s family, they gave them back when the house was rebuilt.

Scenes from Bonniebrook: O’Neill’s recreated studio — the image with the walls painted green — is located on the top floor and is complete with one of her easels.

Scenes from Bonniebrook: O’Neill’s recreated studio — the image with the walls painted green — is located on the top floor and is complete with one of her easels.

They fill the distinctive structure that takes visitors to another time. Yet, its challenges are evident.

Some, like a long streak of water damage — strangely similar to O’Neill’s distinctive handwriting — mars a wall in a bedroom. Other issues, like the lack of air conditioning, are especially felt at specific times.

And then there’s the roof, which reflects a very acute need: The need for a new one to continue the landmarks’ insurance coverage. Their deadline: June.

That project is estimated at about $25,000, a figure of which the society has about $1,000.

The volunteer board is working on fundraising ideas and grant applications, but otherwise, income is limited. Most comes through ticket sales and the gift shop, which is filled with Kewpie and O’Neill memorabilia (as well as a garage-sale-style offerings) that are donated to the site.

Why this cause?

Artists from Springfield Plein Air visited Bonniebrook in May.

Artists from Springfield Plein Air visited Bonniebrook in May.

Even though O’Neill is not physically alive, her spirit lives through the beauty and peace offered to guests.

There are walking trails, which are free to enjoy and are open even when the visitors center is not. The gardens are maintained in connection with local master gardeners.

A monthly Bluegrass jam is now held seasonally on the third Saturday of the month; it’s free to attend, although the home is not available for tours during that time.

On a bright May day, a group from Springfield Plein Air visited, painting and sketching the world as they saw it.

“It’s nice just to get outside in nature, that’s what I like about it,” says Eric Bosch, one of the artists.“Despite the fact that I came out to nature, I ended up drawing (her house). Architecturally it’s really interesting, so that’s what I ended up doing.”

Those literal points of fascination mesh with O’Neill’s legacy: Bridging modern-day benefits with her lasting impact on the world.

“I guess for me, it's the family ties, but it's also looking at her life,” says Pritchard. “Just think: She did a lot for the women's suffrage movement. (Women) might not be able to vote as women today if it hadn't been for her big push. It’s that for me, and it's also to keep teaching the next generation hopefully about what a strong woman can do."

Want to visit?

Click here to read more about Bonniebrook.