When the contents of the wooden Wommack Mill were sold at auction in April 1970, the sale bill sounded like the end of an era. It signified the conclusion of the nearly century-old mill’s working days, a good-bye that came with the death of its owner and a world where such landmarks were fast fading away.

It’s also a reminder that things aren’t always as they seem at the time. Because not long after that sale, Dan and Betty Manning arrived in Fair Grove, a community in the northeastern corner of Greene County of about 1,500 people today.

Now in their late 70s, the couple moved to the Ozarks from California in 1974 seeking a rural environment to raise their children. A lasting connection with the community was quick: In a 1980 Springfield Daily News article, a 36-year-old Dan Manning said, “‘I was probably divinely led to Fair Grove.”

It’s where they found kindred spirits – starting with Jerry Thomas, a man with generations of local lineage – who banded together to restore the mill; preserve the history of their adopted home; start a fall festival as well as an ice cream social (both now nearly 50 years running); and form the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society.

Today, the mill is a centerpiece in the small-but-strong historical area of Fair Grove, which features shops like Festoons & Filigree for antiques, Monroe House for clothing and Monroe Coffee Co. for caffeine; and Time Travel Cafe, a diner focused on “All American Diner Food,” as its website says.

The mill is there due to the dedication of so many: Those who ran it for nearly a century, those who restored it in incremental moments, as well as those who keep it moving forward through the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society.

“Old-timers really helped us,” says Manning of their start on mill work in the ‘70s. “They’d come down and tell us things; they couldn't do a lot, but they’d tell us things, and they’d encourage us.

“They’d say, ‘That ain’t the way we done that.’ I’d say, ‘Why don’t you show me how to use this tool?’ And then I’d screw it up and they’d say, ‘Give me that’ and then they’d show me."

Fair Grove mill begins

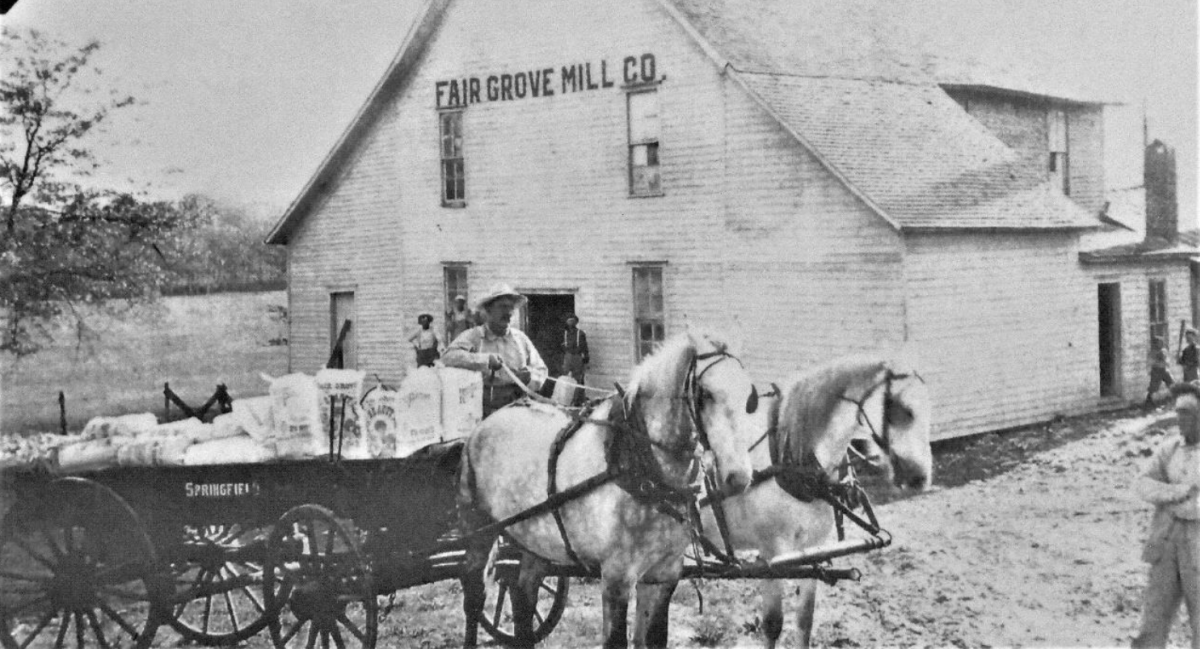

The Fair Grove mill is shown circa 1915. (Courtesy of Kay Mowrey and the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society)

The mill had its start long before the Mannings arrived in Missouri and the Wommack family acquired the business. It opened as the Boegel and Hine Flour Mill in 1883, a time when Fair Grove was a bustling little town, notes the "History of Greene County," a book published the same year as the mill's start:

“There are now in Fair Grove two good stores, one drug store, two blacksmith shops, a flourishing Masonic lodge, two churches (Baptist and Cumberland Presbyterian), and a number of neat dwellings," its pages preserve, also noting that the town’s first school began in the 1840s.

As were other parts of the Ozarks, the rural Greene County landscape was also agricultural. According to the mill's application for the National Register for Historic Places, in the late 1800s Greene County was in Missouri's top five in the production of corn and wheat: "third in corn acreage, fourth in wheat acreage, and third in the two combined."

That was an era when mills were destinations across the Ozarks, but practical ones as opposed to the romantic attractions they are today. Farmers needed places to grind their wares, and mills were created as places to do this — and, along the way, also became social centers.

While mills across the region each offer unique elements, a defining element at Fair Grove’s is its large storage silos, which were added between 1915 and 1917 and together had a capacity of 11,600 bushels.

“They were made of creek gravel and portland cement,” notes Manning in "Grist Mill in Fair Grove," a document about the mill's history that he created in 2022. In it, he also includes that they were built by Joe McMillan of Republic.

"The silos were filled with wheat that became moldy, and the spoiled grain was sold for hog feed,” Manning writes. “They were never filled again. Their presence became an important factor in Fair Grove Mill being recognized for inclusion as a significant historic site in Missouri.”

Silos still stand today — but as a visual reminder rather than a useful tool.

Time brought much change to the mill, evolving its power source, product, name and even reason for existence.

Never a water mill, it was powered by steam until 1923, when an electric motor was added. Later, it was operated with a gasoline engine before diesel took over as the final power source.

Eventually, Wommack Mill – named for its last owners, Clifford and Ethel Wommack, as well as at least two of his cousins – didn’t produce flour. It created feed for animals.

That switch occurred because people began buying more food in grocery stores as opposed to growing their own. Perhaps it was also prompted by a need for innovation after the Great Depression, during which business got so bad that Clifford Wommack had to temporarily take another job.

“The Depression hit and he went to be a trucker for the grocery,” said Helen Highfill, his daughter, in a 1982 Springfield Leader & Press article about the mill.

The change led to a business model that lasted through the 1960s.

“It’s better to wear out than rust out, according to Mr. and Mrs. Clifford E. Wommack of Fair Grove,” noted a 1964 article in the Springfield Daily News. “They’re shown busily sacking feed mixed in the mill which they operate alone, at ages 74 (for him) and 71. Mrs. Wommack ‘swings’ a sack of grain or feed the way most housewives half her age swing a broom.

“Cattle and hog farmers from over the area bring their grains for grinding and mixing – or have them mixed according to their own formula."

Closing and preserving the mill

When Clifford Wommack died in 1969, his widow held an auction to sell off as much from the mill as possible. Yet she retained ownership of the property, which she held when the Mannings moved to town five years later.

Local history quickly became a focus for the young couple. They set about rehabbing an old house in the center of town, and soon worked with the aforementioned Thomas and others to restore the town’s historical cemetery, which had largely been forgotten. Their efforts led to the start of the Fair Grove Historical Society in 1977.

They also rescued what was said to be the “last pair of working mule team in Fair Grove,” in 1978, purchasing them at auction when their owner died. Pete and Jack, as they were known, lived out the remainder of their lives in a pasture near the mill – except for when they were periodically working or serving as community ambassadors at regional events.

“They took turns providing power for the sorghum syrup, plowed many local gardens, never missed a local parade or reunion and were the subject of the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society logo,” noted a Sunday News and Leader article upon the second’s death in 1982.

By then, the mill was in very poor shape. It was such a liability that Ethel Wommack had painted “no trespassing” on the front to try to keep liability from potential accidents at bay. But locals had hope, and in 1984, it was sold to the historical society for $6,000.

“It has been the center for community commerce and social meetings of farmers bringing their produce to market for almost a hundred years,” said Jerry Thomas in a 1982 Springfield Leader & Press article about the mill. “It would be a shame to see a structure so meaningful to our Ozarks heritage, simply rot to the ground like so many others have.”

In 1986, the mill — listed under its original name of Boegel and Hine Flour Mill — was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and work gradually was done to stabilize the aging structure.

One of the largest projects was when the mill was raised from where it sat so a new foundation could be installed, a task that was accomplished at the hands of Amish carpenters in the late 1980s.

Efforts to raise money and awareness led to the start of annual events now decades in existence. In the late ‘70s, an ice cream social was held to help raise money; it is still held on the third Saturday in July.

A look at the Fair Grove Car Show, held annually in the 1980s. If you look closely, you’ll see a truck bed full of trophies. (Photo by Dan Manning; courtesy of the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society)

Another touchpoint is the Fair Grove Heritage Reunion, which started in 1979. It brings crafters, artisans and "tens of thousands" of curious attendees to downtown Fair Grove. The reunion continues annually on the last full weekend in September.

In 2023, the mill will be open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 23 and from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Sunday, Sept. 24, with grinding demonstrations also held during those windows.

While some things at the reunion have changed with time – for example, they no longer have hog butchering – demonstrations of old-time skills remain a focus for the festival. Examples planned for 2023 include spinning, blacksmithing, and quilting. The latter – along with making butter – offer kids a chance to participate.

“It’s funny how even the parents go, ‘Oh, I remember doing that as a kid,” says Mary Terry, board president of the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society, of shaking cream to make butter. “Of course, they get to taste that on a cracker.”

The festivities also feature a parade (with lots of candy for the kids, Terry says) and an opportunity for inclusivity – although politicians are asked to skip displaying signs.

“I’ve had complaints over the years about ‘Why did you allow this? Why did you allow that?” says Terry. “It’s a Fair Grove parade. Anybody is welcome to it. It’s part of the fun.”

Future of the mill

Betty and Dan Manning pose at the mill with Mary Terry, board president of the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society.

It’s been nearly 50 years since restoration efforts at the mill began. Those years of work – to stabilize the structure, and fill it with equipment – have resulted in its current status as a touchpoint with the past, as well as a relevant piece of the present.

Outside the mill, thousands have seen the structure through professional photos, including through the 2023 Shell Rotella SuperRigs calendar.

"They have a big-rig show down in Branson, and we were one of the sites for the photos," says Terry. "They spent the afternoon shooting a big-rig here. So literally, the Ozarks — and us — were seen throughout the United States on this calendar.

"I asked the gentlemen how he found out about us, and he said, 'I just Googled historic places."

Walking into the wooden landmark, historical displays and representative equipment help tell the mill’s story – both as a mill, and as a preservation project.

“All the framework is authentic. The original first floor is right here,” says Manning. “Everything else was rotted or worn out, but this floor was taken off the second floor. So it’s authentic to the building. We just put down rough-cut oak for a subfloor here. There’s lots of room for more work on the second floor.”

The mill isn’t 100% the same as it once was. As Manning noted, the second floor still needs work; although there is some milling equipment up there, it’s not open to the public. Among other refurbishment efforts, a porch was added. And in 2001, a U.S. flag was installed on the front of the mill days after 9/11. As flags have weathered, they’ve been replaced and retired.

“Hopefully, an American flag will always be on display at Fair Grove Mill,” notes Manning’s historical document.

Scenes from the mill

At times, the equipment gets fired up, but the structure has become part of lives in other ways: Church services are regularly held outdoors, and students and families gather for photos in moments of significance.

“High school kids are coming here on prom night, graduation night. A lot of them (take pictures) here,” says Betty Manning. “One year, during COVID, they actually had the senior prom out here. They rented a giant tent. It just warmed my heart.”

Photos peer from walls, reminding of the moments that brought the mill to where it is today.

“Mrs. Wommack had most of these old photographs, and of course we took photographs as we went along too,” says Manning, pointing to black and white photos that hang on the walls.

And faded overalls hang on a wall in back, honoring those local people who supported the project to fruition.

“It means a lot to us that these old-timers accepted us and our dreams instead of just saying, ‘Oh, you know kids,’” says Betty Manning.

Overalls hang in the mill in appreciation for certain individuals’ contributions in its restoration.

Overalls hang in the mill in appreciation for certain individuals’ contributions in its restoration.

The faded fabric also represents a reminder that time marches on.

Like many who remembered the mill in action, Thomas, the aforementioned advocate, is also gone. He died in 2015, yet words in his obituary preserve his spirit forever.

“He was instrumental in the preservation of the Wommack Mill,” his obituary included. “In 2000, he received the key to the City of Fair Grove. He loved Fair Grove. Its history and future will be forever molded by all his hard work.”

The Mannings no longer live in Fair Grove. Now in their late 70s, they retired from active work at the mill and festival and moved to Springfield, about 20 miles south from their adopted hometown, to be closer to family.

That’s not to say oversight of the mill is gone. It’s just part of marking a new phase for the mill’s future.

Led by President Terry, a group of dedicated individuals oversee the historical society’s property, which in addition to the mill, includes a cabin, a representative schoolhouse, a museum and the old cemetery. They also plan the annual festival and ice cream social with the help of many volunteers.

“I think some people don’t realize the acreage we do own and manage, and have to take care of – that’s expensive to do,” says Terry. “We don’t rent the inside of the mill, but we do rent the porch. We have had funerals here, and we’ve had weddings both, and you can come here any time.”

While the maintenance of more than seven acres isn’t always easy, it’s meaningful to continue the story.

"It's the history of this community," says Terry of the mill. "I've been here almost my whole life — walking around, seeing those overalls, it's a carry-on of what these men and women did. It's just the respect for them."

Want to visit?

The Wommack Mill will be open during the 2024 Fair Grove Heritage Reunion Sept. 28-29. It’s also open during workdays on the third Saturday of each month and tours are generally available between 9 a.m. and noon. Other group tours may be arranged by calling 417-759-2807.

For more information about the Fair Grove Historical and Preservation Society, click here to visit its website, and here for its Facebook page.

The creation of this story is funded by a partnership between Ozarks Alive and I Love Springfield, MO!, formally known as the Springfield Missouri Convention & Visitors Bureau.